I was out for my very last hunting trip my Roman hunting buddy Marcus in a large wheat field, trying to find some additional 4th century Roman bronze coins. I had found about 40 in this one area of a wheat field three months prior, and now I wanted to see if any where left. I did not find any more bronze Romans, but I did come across a small penny-sized silver coin that I had never seen before. It bore none of the usual markings of Roman coins, and had Greek letters instead of Latin, and was adorned with a cow on one side. After some research I discovered that the coin was a Greek Drachm from the Illyrian city of Apollonia in the 1st century BC.

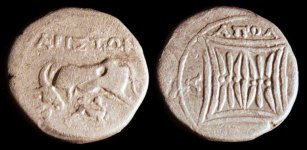

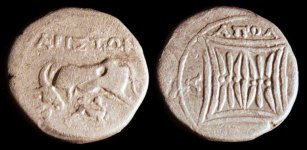

The obverse side shows a cow facing left, looking back to the right as a calf suckles. The top has a legend that reads “APIΣTΩN” which translates to Ariston, the moneyer who was overseeing the mint in Apollonia at this time.

The reverse has a convex double-stellate pattern with petal rays and seven dots, enclosed in a single line round border. Only two sides of the reverse legend are readable, but that is enough to correctly ID the coin. The top legend reads “AПOΛ” which translates to Apollonia, where the coin was minted. The rest of the legend around the coin would have read “AI NE A”. Ainea was the name of the Magistrate of Apollonia. The coin was struck in the last period of Greek coin minting in Roman controlled Apollonia – which would put the date to around 80BC.

The cow/calf fertility symbol is of Euboean origin. The symmetrical geometrical pattern is most probably a schematic representation of the two stars of the Dioscuri, in Greek and Roman mythology, twin deities who aided shipwrecked sailors and received sacrifices for favorable winds. In Latin, we know them as Castor and Pollux, twin stars located in the Constellation Gemini.

Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by the Illyrians. The Romans conquered the region in 168 BC in the aftermath of the Illyrian Wars. "Illyria" is thus a designation of a roughly defined region of the western Balkans as seen from a Roman perspective, just as Magna Germania is a rough geographic term not delineated by any linguistic or ethnic unity. The term is sometimes used to define an area (now in modern Albania) north of the Aous valley.

The Romans defeated Gentius, the last king of Illyria, at Scodra (in present-day Albania) in 168 BC and captured him, bringing him to Rome in 165 BC. Four client-republics were set up, which were in fact ruled by Rome. Later, the region was directly governed by Rome and organized as a province, with Scodra as its capital.

The Roman province of Illyricum replaced the formerly independent kingdom of Illyria. It stretched from the Drilon river in modern Albania to Istria (Croatia) in the west and to the Sava river (Bosnia & Herzegovina) in the north. Salona (near modern Split in Croatia) functioned as its capital.

After crushing a revolt of Pannonians and Daesitiates, Roman administrators dissolved the province of Illyricum and divided its lands between the new provinces of Pannonia in the north and Dalmatia in the south. Although this division occurred in 10 AD, the term Illyria remained in use in Late Latin and throughout the medieval period.

Apollonia

Apollonia was an ancient Greek city and colony in southern Illyria, now in modern-day Albania, located on the right bank of the Aous river; its ruins are situated in the Fier region, near the village of Pojani. It was founded in 588 BC by Greek colonists from Kerkyra (Corfu) and Corinth, and was perhaps the most important of the several classical towns known as Apollonia (Απολλωνία), so named in honor of the god Apollo.

Aristotle considered Apollonia an important example of an oligarchic system, as the descendants of the Greek colonists controlled the city and prevailed over a large serf population of mostly Illyrian origin. The city grew rich on the slave trade and local agriculture, as well as its large harbor, said to have been able to hold a hundred ships at a time. The remains of a late sixth-century temple, located just outside the city, were reported in 2006; it is only the fifth known Hellenic temple found in present-day Albania.

In 229 BC it came under the control of the Roman Republic, to which it was firmly loyal. In 148 BC Apollonia became part of the Roman province of Macedonia, specifically of Epirus Nova. In the civil war between Pompey and Julius Caesar it supported the latter, but fell to Marcus Iunius Brutus in 48 BC.

Apollonia flourished under Roman rule and was noted by Cicero in his Philippics as "magna urbs et gravis", a great and important city. Its decline began in the 3rd century AD, when an earthquake changed the path of the Vjosa river, causing the harbor to silt up and the inland area to become a malaria-ridden swamp.

The city seems to have taken a backseat with the rise of the coastal city of Vlora. It was "rediscovered" by European classicists in the 18th century, though it was not until the Austrian occupation of 1916–1918 that the site was investigated by archaeologists. Their work was continued by a French team between 1924–1938. Parts of the site were damaged during the Second World War. After the war, an Albanian team undertook further work from 1948 onwards, although much of the site remains unexcavated to this day. Some of the team's archeological discoveries are on display within the local monastery, and other artefacts from Apollonia are in the capital Tirana. Unfortunately, during the anarchy that followed the collapse of the communist regime in 1990, the archeological collection was plundered

So what may have brought this coin from the Adriatic all he way up to the northern Serbian Danube region at the beginning of the 1st c. BC?

In fact, the link between the Balkan Celts and the Adriatic coast, and the circumstances which led to large amounts of these ‘Illyrian’ and other Roman issues reaching the territory of the (Scordisci tribe) Celts in Serbia and Bulgaria is well documented in Roman sources. By the beginning of the 1st c. BC the Roman forces on the Balkans were feeling the strain of the apparently endless barbarian attacks from the north. In 90 BC the dam finally burst and, confronted by yet another Scordisci Celtic attack, the Roman borders disintegrated. The events which followed are described by the Roman historian Florus. The Celtic tribes, now joined by the Maidi and Denteletes, as well as the Dardanii tribes, swarmed through Macedonia, Thessaly and Dalmatia, even reaching the Adriatic coast. According to the Roman historian: “Throughout their advance they left no cruelty untried, as they vented their fury on their prisoners; they sacrificed to their gods with human blood; they drank out of human skulls; by every kind of insult inflicted by burning and fumigation they made death more foul; they even forced infants from their mother’s wombs by torture”. In this litany of evil atrocities committed by their enemies, special mention is reserved by the Romans for the Celts – “The cruelest of all the Thracians were the Scordisci, and to their strength was added cunning as well”.

While much of the above account may be put down to Roman hysteria and exaggeration, it is clear that from 90 BC onwards the empire had lost de facto control over large parts of the Balkans and northern Greece. By 88 BC, i.e. 2 years after the collapse of the Roman borders in Macedonia, the Scordisci and their allies had swept through northern Greece and reached Dodona in Epirus (southern Albania/Norrthermn Greece today), where they destroyed the temple of Zeus. By the winter of 85/84 BC they had penetrated as far as Delphi, where the most sacred of Greek temples was once again destroyed.

So the area was awash in bloodshed and Scordesci Celts were rampaging all over the Illyian lands, bringing plundered loot back to their own homelands, which is where I found this lovely coin. Some Scordesci warrior brought his pillaged coins back home and burried them for safe keeping - where upon two thousand years later a plow scattered them into a modern day wheat field. And I walked over one of them.

The obverse side shows a cow facing left, looking back to the right as a calf suckles. The top has a legend that reads “APIΣTΩN” which translates to Ariston, the moneyer who was overseeing the mint in Apollonia at this time.

The reverse has a convex double-stellate pattern with petal rays and seven dots, enclosed in a single line round border. Only two sides of the reverse legend are readable, but that is enough to correctly ID the coin. The top legend reads “AПOΛ” which translates to Apollonia, where the coin was minted. The rest of the legend around the coin would have read “AI NE A”. Ainea was the name of the Magistrate of Apollonia. The coin was struck in the last period of Greek coin minting in Roman controlled Apollonia – which would put the date to around 80BC.

The cow/calf fertility symbol is of Euboean origin. The symmetrical geometrical pattern is most probably a schematic representation of the two stars of the Dioscuri, in Greek and Roman mythology, twin deities who aided shipwrecked sailors and received sacrifices for favorable winds. In Latin, we know them as Castor and Pollux, twin stars located in the Constellation Gemini.

Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by the Illyrians. The Romans conquered the region in 168 BC in the aftermath of the Illyrian Wars. "Illyria" is thus a designation of a roughly defined region of the western Balkans as seen from a Roman perspective, just as Magna Germania is a rough geographic term not delineated by any linguistic or ethnic unity. The term is sometimes used to define an area (now in modern Albania) north of the Aous valley.

The Romans defeated Gentius, the last king of Illyria, at Scodra (in present-day Albania) in 168 BC and captured him, bringing him to Rome in 165 BC. Four client-republics were set up, which were in fact ruled by Rome. Later, the region was directly governed by Rome and organized as a province, with Scodra as its capital.

The Roman province of Illyricum replaced the formerly independent kingdom of Illyria. It stretched from the Drilon river in modern Albania to Istria (Croatia) in the west and to the Sava river (Bosnia & Herzegovina) in the north. Salona (near modern Split in Croatia) functioned as its capital.

After crushing a revolt of Pannonians and Daesitiates, Roman administrators dissolved the province of Illyricum and divided its lands between the new provinces of Pannonia in the north and Dalmatia in the south. Although this division occurred in 10 AD, the term Illyria remained in use in Late Latin and throughout the medieval period.

Apollonia

Apollonia was an ancient Greek city and colony in southern Illyria, now in modern-day Albania, located on the right bank of the Aous river; its ruins are situated in the Fier region, near the village of Pojani. It was founded in 588 BC by Greek colonists from Kerkyra (Corfu) and Corinth, and was perhaps the most important of the several classical towns known as Apollonia (Απολλωνία), so named in honor of the god Apollo.

Aristotle considered Apollonia an important example of an oligarchic system, as the descendants of the Greek colonists controlled the city and prevailed over a large serf population of mostly Illyrian origin. The city grew rich on the slave trade and local agriculture, as well as its large harbor, said to have been able to hold a hundred ships at a time. The remains of a late sixth-century temple, located just outside the city, were reported in 2006; it is only the fifth known Hellenic temple found in present-day Albania.

In 229 BC it came under the control of the Roman Republic, to which it was firmly loyal. In 148 BC Apollonia became part of the Roman province of Macedonia, specifically of Epirus Nova. In the civil war between Pompey and Julius Caesar it supported the latter, but fell to Marcus Iunius Brutus in 48 BC.

Apollonia flourished under Roman rule and was noted by Cicero in his Philippics as "magna urbs et gravis", a great and important city. Its decline began in the 3rd century AD, when an earthquake changed the path of the Vjosa river, causing the harbor to silt up and the inland area to become a malaria-ridden swamp.

The city seems to have taken a backseat with the rise of the coastal city of Vlora. It was "rediscovered" by European classicists in the 18th century, though it was not until the Austrian occupation of 1916–1918 that the site was investigated by archaeologists. Their work was continued by a French team between 1924–1938. Parts of the site were damaged during the Second World War. After the war, an Albanian team undertook further work from 1948 onwards, although much of the site remains unexcavated to this day. Some of the team's archeological discoveries are on display within the local monastery, and other artefacts from Apollonia are in the capital Tirana. Unfortunately, during the anarchy that followed the collapse of the communist regime in 1990, the archeological collection was plundered

So what may have brought this coin from the Adriatic all he way up to the northern Serbian Danube region at the beginning of the 1st c. BC?

In fact, the link between the Balkan Celts and the Adriatic coast, and the circumstances which led to large amounts of these ‘Illyrian’ and other Roman issues reaching the territory of the (Scordisci tribe) Celts in Serbia and Bulgaria is well documented in Roman sources. By the beginning of the 1st c. BC the Roman forces on the Balkans were feeling the strain of the apparently endless barbarian attacks from the north. In 90 BC the dam finally burst and, confronted by yet another Scordisci Celtic attack, the Roman borders disintegrated. The events which followed are described by the Roman historian Florus. The Celtic tribes, now joined by the Maidi and Denteletes, as well as the Dardanii tribes, swarmed through Macedonia, Thessaly and Dalmatia, even reaching the Adriatic coast. According to the Roman historian: “Throughout their advance they left no cruelty untried, as they vented their fury on their prisoners; they sacrificed to their gods with human blood; they drank out of human skulls; by every kind of insult inflicted by burning and fumigation they made death more foul; they even forced infants from their mother’s wombs by torture”. In this litany of evil atrocities committed by their enemies, special mention is reserved by the Romans for the Celts – “The cruelest of all the Thracians were the Scordisci, and to their strength was added cunning as well”.

While much of the above account may be put down to Roman hysteria and exaggeration, it is clear that from 90 BC onwards the empire had lost de facto control over large parts of the Balkans and northern Greece. By 88 BC, i.e. 2 years after the collapse of the Roman borders in Macedonia, the Scordisci and their allies had swept through northern Greece and reached Dodona in Epirus (southern Albania/Norrthermn Greece today), where they destroyed the temple of Zeus. By the winter of 85/84 BC they had penetrated as far as Delphi, where the most sacred of Greek temples was once again destroyed.

So the area was awash in bloodshed and Scordesci Celts were rampaging all over the Illyian lands, bringing plundered loot back to their own homelands, which is where I found this lovely coin. Some Scordesci warrior brought his pillaged coins back home and burried them for safe keeping - where upon two thousand years later a plow scattered them into a modern day wheat field. And I walked over one of them.